The following article by Mark Buchanan was recently published on Medium. It discusses recent analysis by Nassim, along with Pasquale Cirillo, of historical warfare statistics. This analysis contradicts the popular idea that future violent wars are unlikely:

Violent warfare is on the wane, right?

Many optimists think so. But a close look at the statistics suggests that the idea just doesn’t add up.

A spate of recent and not so recent books have suggested that “everything is getting better,” that the world is getting more peaceful, more civilized, and less violent. Some of these claims stand up. In his book The Better Angels of Our Nature, psychologist Steven Pinker made the case that everything from slavery and torture to violent personal crime and cruelty to animals has decreased in modern times. He presented masses of evidence. Such trends, it would certainly seem, are highly unlikely to be reversed.

Pinker also suggested — as have others, including historian Niall Ferguson — that something big has changed about violent warfare since 1945 as well. Here too, the world seems to have become much more peaceful, as if war is becoming a thing of the past. As he wrote,

… wars between great powers and developed nations have fallen to historically unprecedented levels. This empirical fact has been repeatedly noted with astonishment by many military historians and international relations scholars…

Pinker admits that this might be a statistical illusion; perhaps we’ve just experienced a recent lull, and war will resume with its full historical fury sometime soon. But he thinks this is unlikely, for a variety of reasons. These include…

the fact that the drop in the frequency of wars among great powers and developed states has been so sudden and massive (essentially, to zero) as to suggest a qualitative change; that territorial conquest has similarly all but vanished in the planning and outcomes of wars; that the period without major war has also seen sharp reductions in conscription, length of military service, and per-GDP military expenditures; that it has seen declines in every exogenous variable that are statistically predictive of militarized disputes; and that war rhetoric and war planning have disappeared as live options in the political deliberations of developed states in their dealings with one another. None of these observations were post-hoc, offered at the end of a fortuitously long run that was spuriously deemed improbable in retrospect; many were made more than three decades ago, and their prospective assessments have been strengthened by the passage of time.

Again, Pinker has gone to lengths to emphasize that none of this proves anything abut future wars. But it is strongly suggestive, he believes, that this is significant evidence for such a belief.

Nassim Taleb criticized Pinker’s arguments a few years ago, arguing that Pinker didn’t take proper account of the statistical nature of war as a historical phenomenon, specifically as a time series of events characterized by fat tails. Such processes naturally have long periods of quiescence, which get ripped apart by tumultuous upheavals, and they lure the mind into mistaken interpretations. Pinker responded, clarifying his view, and the quotes above come from that response . Pinker acknowledged the logical possibility of Taleb’s view, but suggested that Taleb had “no evidence that is true, or even plausible.”

That has now changed. Just today, Taleb, writing with another mathematician, Pasquale Cirillo, has released a detailed analysis of the statistics of violent warfare going back some 2000 years, with an emphasis on the properties of the tails of the distribution — the likelihood of the most extreme events. I’ve written a short Bloomberg piece on the new paper, and wanted to offer a few more technical details here. The analysis, I think, goes a long way to making clear why we are so ill-prepared to think clearly about processes governed by fat tails, and so prone to falling into interpretive error. Moreover, it strongly suggests that hopes of a future with significantly less war are NOT supported by anything in the recent trend of conflict infrequency. The optimists are fooling themselves.

Anyone can read the paper, so I’ll limit myself to simply summarizing a few of the main points:

- Following many historians, Cirillo and Taleb use the number of casualties as a measure of the size of a conflict. Obviously, since the human population has grown with time, larger wars have become possible. So, they sensibly treat the data in a fractional sense — looking at the number of deaths as a fraction of the human population.

- For nearly more than 50 years, going back to Lewis Fry Richardson, it’s been known that the cumulative distribution of wars by size follows a rough power law, the number of events larger than size S being proportional to 1/S raised to an exponent α. This is also an approximation, of course, because there is an absolute maximum possible size for a conflict — it can’t be more than then entire population. Hence, the power law form can only hold over a certain range. To take this into account, Cirillo and Taleb also rescale the data to take into account the finite size of the human population.

- Having done this, they find using various statistical methods that α falls within the range 0.4 to 0.7. For maximum sensitivity in the statistical tests, they derive this by focusing mostly on the largest wars over the 2000 years, those equivalent (in today’s numbers) to at least 50,000 casualties.

- Note on the value of α — this is smaller than the exponent known to hold for either earthquakes or financial market fluctuations. This implies that statistics of wars is even more prone to large fluctuations than these other processes, which are of course highly erratic themselves.

- It also implies that the sample mean over any period is NOT a very useful statistic for estimating the TRUE mean of the underlying statistical process. For example, it turns out that, for a process following this statistical pattern, one should expect fully 96% of all observations to fall below the true mean of the process. This brings home just how non-Gaussian and non-normal this process is. We’re used to thinking that, if we observe instances from some random process, we ought to (very crudely) see events about half above and half below the mean. Instead, in this process, one should expect that almost all observations will be below, and even far below, the actual mean. We almost always see fewer wars than we, in a sense, should. The process is set up almost perfectly to make an observer complacent about the possibility of large events.

- Related to the above, it also turns out to be >90% certain that the true mean of the process is higher than the observed mean. What we have seen in the record of wars over the past 70 years, for example, almost certainly offers an underestimate of the true likelihood of wars. The statistical process makes rare but large events so likely that looking forward on the basis of recent past observations is a recipe for unwarranted optimism. In actual numbers, Cirillo and Taleb find that the true expected mean — say, the number of deaths we should expect over the next half century — is actually about three times higher than what we’ve seen in the past.

There are quite few other gems in the analysis, but these seem to me to be the most important.

One final thing, and maybe this is most important. Cirillo and Taleb make a strong argument that the quantity that one should study and try to estimate from the statistics is the tail exponent α (see point 5 above). This is certainly not easy to estimate, and it takes a lot of data to get even a crude estimate, but working with α is a much better way of getting at the true mean of the process than working with the sample mean over various periods. Looking at past events, and estimating the average number over any period, is simply a bad way to go about thinking about any process of this kind. The sample mean is NOT a mathematically sound estimate of the true mean of the process. For more on this, see Taleb’s comments at the top of the 3rd page of his earlier criticism of Pinker’s argument.

And that, I think, is pretty good reason to believe that all talk of the dwindling likelihood of wars based on recent past experience is mostly based on illusion and people telling themselves convincing but probably unfounded stories. Sure it looks as if things are getting more peaceful. But, looking at the mathematics, that’s exactly what we should expect to see, even if we’re most likely due for a much more violent future.

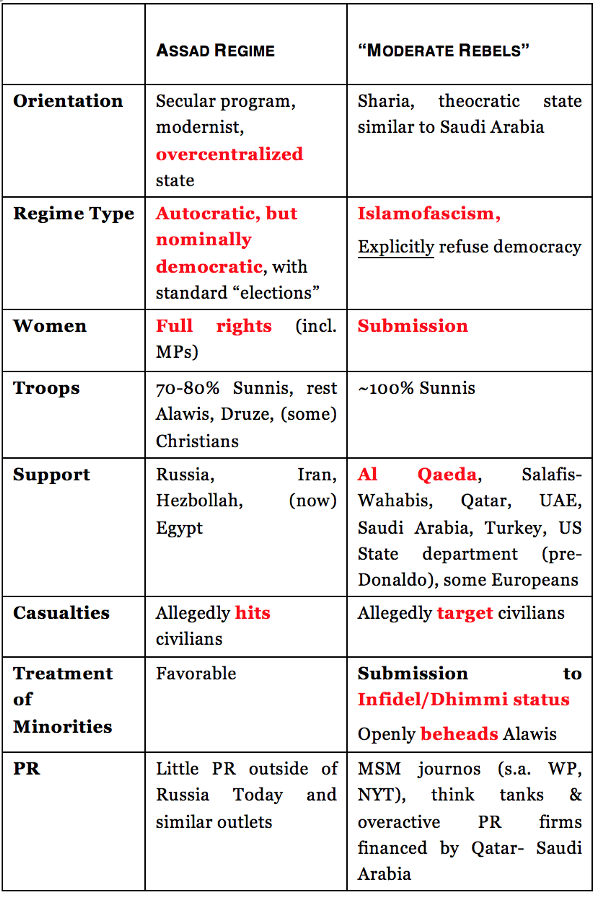

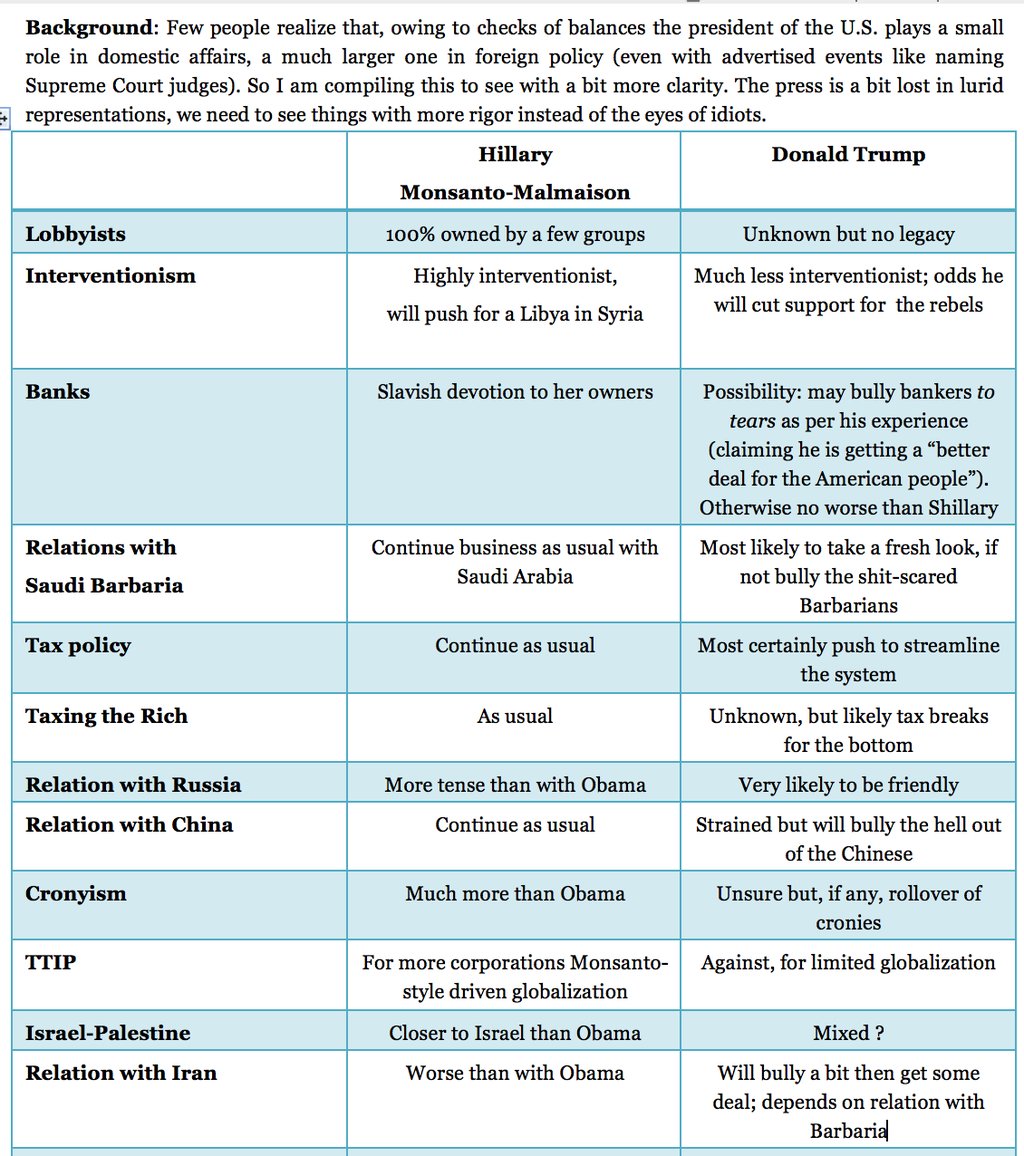

He also followed up with these tweets: “Hillary and Bush have done the most to harm minority populations in the Levant & Iraq since Genghis Khan.” “2/What I mean by rigorous is not making assumptions/ certainties when there is uncertainty. Shillary offers certainties, Trump fewer ones.”

He also followed up with these tweets: “Hillary and Bush have done the most to harm minority populations in the Levant & Iraq since Genghis Khan.” “2/What I mean by rigorous is not making assumptions/ certainties when there is uncertainty. Shillary offers certainties, Trump fewer ones.”